By Kevin Boyd

First published on the Come Sing It Plain… website, February 2019

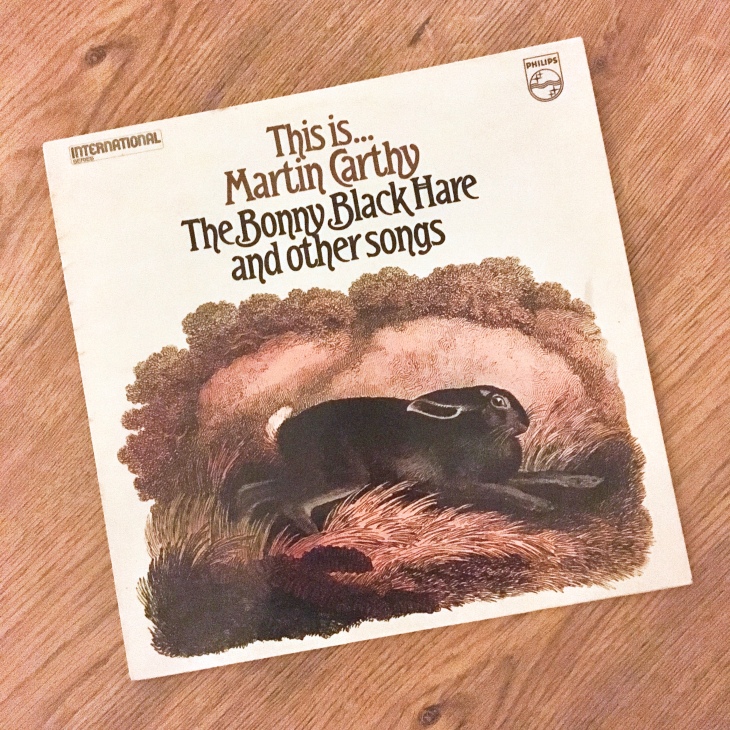

“This is… Martin Carthy – The Bonny Black Hare and other songs” was one of a couple of major compilations of material from Carthy & Swarbricks 1960s recordings to appear in the early ‘70s. It was also the first Martin Carthy album I ever heard about 15 years after its original 1971 release, but I’ve never actually owned a copy until today.

I’d been obsessing over The Watersons for months after hearing them by accident on Andy Kershaw’s Radio 1 show in August 1986 and had borrowed everything of theirs I could find in my local record library. At the time, I worked as a printer and my mate and colleague Allan Wilkinson – you may know his tireless work as head honcho at Northern Sky – suggested I check out Martin Carthy: “He sings the same type of songs but solo and plays great guitar. You’ll like him”.

I wasn’t interested. Not one bit! The thing I loved most about The Watersons was precisely their lack of guitars (or any instrumentation, for the most part) and the thing that set them apart was their inspiring harmonies. How could one bloke warbling on his own to a guitar accompaniment ever match the intensity of a Watersons album? I wasn’t having any of it, so I forgot about this “Martin McCarthy” bloke for a while.

Eventually, when it became clear I’d exhausted the record library’s supply of Watersons releases – this was in the pre-CD era when most mainstream record shops simply didn’t stock folk music – I took the plunge and borrowed a Martin Carthy album. I’ve no idea why it was this particular album, I suspect it was the only one they had available at the time. The fact that it was a cassette copy I borrowed would seem to back this up – I’d always prefer vinyl back then given the option.

I don’t recall what I thought of Side One – The Fowler; Brigg Fair; The Barley Straw; Byker Hill; John Barleycorn; Streets Of Forbes. There was no Road to Damascus moment just yet, but I must have been impressed, or perhaps intrigued, enough to turn over for Side Two because I know I got as far as Ship in Distress, Jack Orion and White Hare. Then the next track started and everything changed…

Anyone growing up in the British Comprehensive schooling system in the 1970s and early-80s will know the excruciating agony of the weekly (if you were lucky – perhaps daily if you were less so!) communal school assembly sing-along. This is where I first learned – and learned to hate – such dross as Kum Ba Yah, All Things Bright And Beautiful, and He’s Got the Whole World In His Hands – the agonising list could go on! And because the Teacher Training Colleges of the ‘60s and ‘70s were breeding grounds not only for our future educators, but also for a future generation of folkies, the repertoire would invariably also be troubled with a smattering of contemporary folk ‘hits’, one of which was Sydney Carter’s Lord Of The Dance.

God, I hated that song! It was an irrational hatred, sure, but a real hatred nevertheless. I should say that I also hated Streets Of London and several of Simon & Garfunkel’s better-known ditties. It didn’t matter that some – probably all – of these were fine songs by any normal standards. The fact we were forced to sing them to insufferable piano or guitar accompaniments instilled a special kind of revulsion in the souls of those pre-pubescent lads and lasses who would much rather be listening to Sex Pistols, The Specials, Big Wheels Of Motown… virtually anything, in fact.

I wasn’t 100 percent certain the ‘Lord Of The Dance’ listed on the cassette cover was the same song I’d learned to despise several years earlier, but within the first few bars it became clear that it was. Then something weird happened… I found myself actually enjoying it. I still don’t know why – all my experience should have told me to hate it but, for reasons I still can’t properly explain, I was strangely fascinated by this odd little quasi-religious song.

Maybe I was finally hearing the song in a new light, or maybe it was just the forceful nature of the performance, driven by Carthy’s occasionally idiosyncratic vocal phrasing and Swarb’s driving fiddle. Whatever it was, it made me sit up and listen in a way I hadn’t quite managed with the previous tracks on the album. When the song ended, I played through the rest of the album – Poor Murdered Woman; Bonny Black Hare – then turned over and started Side One again, this time with a renewed interest in the words, their stories, the phrasing and the rhythmic quality to the guitar playing.

Ultimately, Lord Of The Dance didn’t last too long in my affections and was fairly quickly supplanted by the likes of John Barleycorn and Byker Hill from this album and a whole list of tracks from many other albums. In fact, it may be true to say that Lord Of The Dance is now one of my least favourite tracks from Martin Carthy’s 1960s albums, but I’m not sure that matters. Along with the other tracks on this album it did its job when I first heard it and got me started on a 30-plus-year passion – some may say near obsession (near? Who am I kidding?) – with Martin Carthy’s music. And today I can finally say I own a copy of the album – albeit on vinyl and not the cassette I originally heard – that changed everything…